As a continuation to last month’s article, this post will explore the impact of artificial intelligence (AI) on the construction industry. If you haven’t read the previous article, you may want to do so before diving into this one. It isn’t very long and provides a background on how I am defining some of the terms I’ll be using in this series of articles on AI.

Recap

To start, let’s review what we learned last time.

Defining artificial intelligence

For the purposes of these articles, I’ve defined AI as software agents that can perceive their environment and take actions to maximize their chances of success at a specific goal. However, a cursory reading will reveal there is no consensus on that or any definition of AI, but this interpretation is general and broad enough to suit our purposes.

Importance of machine learning to AI

The chief difference between directed software solutions and AI is the latter’s ability to improve its responses over time by “learning.”

Methods of machine learning

As last month’s article explained, machines usually learn through interaction with datasets and examples provided by humans to train them. The article also explored deep learning that mimics the way the brain works by breaking problems and responses into smaller pieces and combining those learned behaviors in different ways.

This month, I’ll be looking at the use of AI and its likely impact on work now and in the future. As always, we will primarily focus on its effect on the construction industry.

They’re coming for our jobs!

As you may expect, machine learning, algorithms, and specialized AI have already started to affect the construction industry, largely in the area of design.

Your job may not be eliminated, but it will change. Certain aspects of your work, such as activities requiring little or no complex thinking, can simply be done better and faster by some form of AI. Removing these job functions may also be welcomed by many professionals.

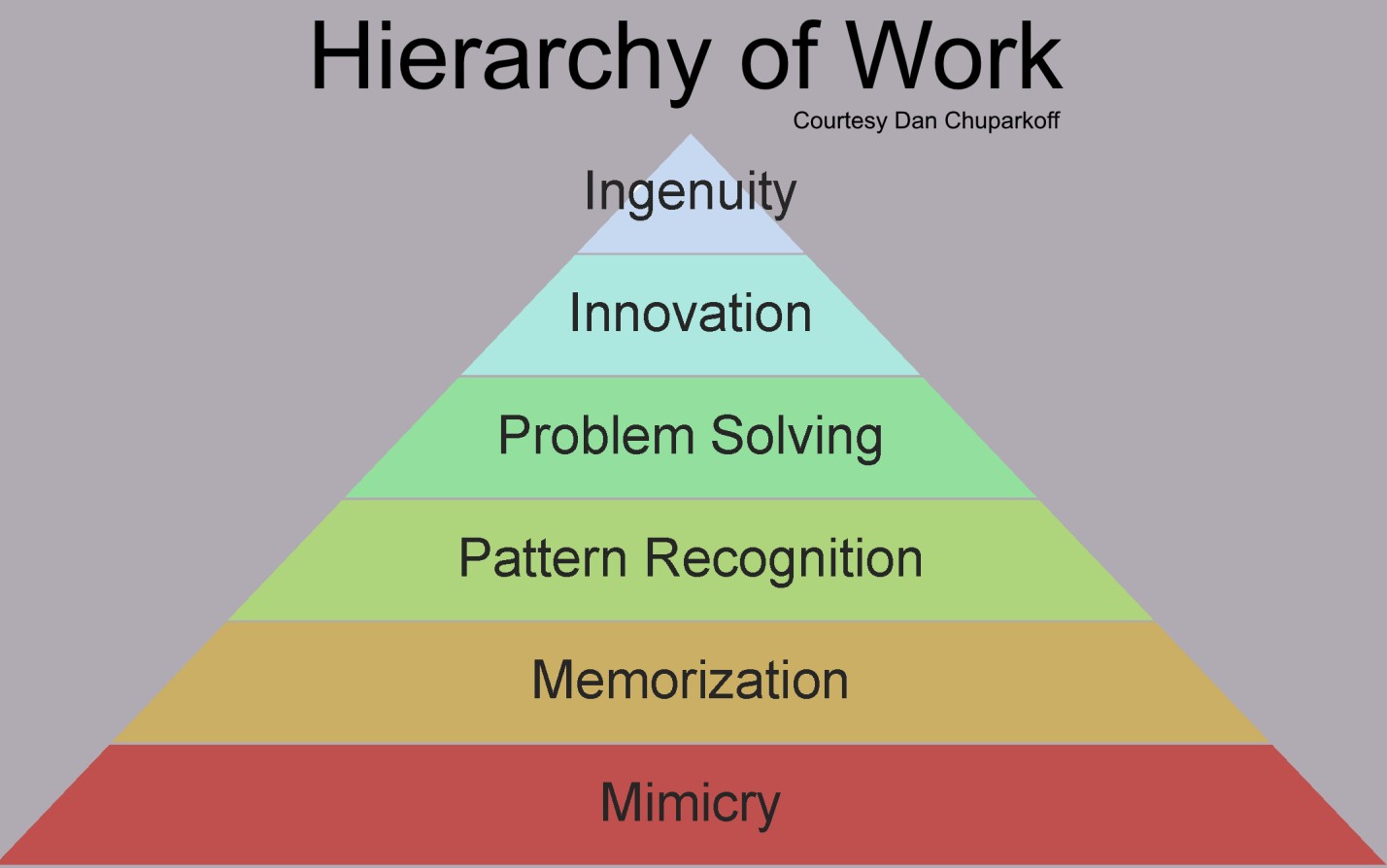

The graphic below is from a presentation given by Dan Chuparkoff at the South by Southwest (SXSW) festival a few years back. It illustrates broad levels of work types most humans engage in. Tasks closer to the bottom are suitable for automated solutions, while the ones on top of the hierarchy may take more specialized knowledge, or in the case of “ingenuity,” combinations of knowledge that are tougher to accomplish with AI.

An illustration of the types of work most humans engage in. Taken from a presentation given by Dan Chuparkoff at the South by Southwest (SXSW) festival.

Most jobs contain tasks that are on different levels of the hierarchy, as a quick examination of your daily workload will reveal. For example, specifiers engage in significant amounts of pattern recognition and problem solving but there is no shortage of memorization and mimicry or even some innovation and ingenuity.

If some of your job functions are listed on the hierarchy, it doesn’t mean you are going to be replaced by automated processes, but it may mean that some work, especially repetitive tasks requiring memorization or pattern recognition in data, may be eased by new software. Many in the design community have benefited from some level of automation in their jobs for years. Model checkers like Solibri and energy analysis tools built into BIM software rely on algorithms to eliminate a lot of tedious work that designers could otherwise be expected to perform. Design of complex facilities like hospitals has also been eased by use of data capture and algorithmic design to help make the layout of spaces and paths better for healthcare workers and patients.

Looking forward, AI has the capacity to replace tedious work, improve quality and constructability of designs earlier in the project schedule, and provide an expanded palette of both solutions and inspiration for designers. Adaptation to new tools will be critical to succeed in a changing design marketplace, so keep an eye on topics like algorithmic and generative design, and the outcomes of machine learning on architecture.

Robots everywhere

Use of AI has even more promise when applied to the construction phase of the project and onsite. For example, as mentioned in a recent The Construction Specifier article, many firms are facing a shortage of trained workers. AI may offer a solution to this and other construction issues, by offering robots and robotic tools that help the human workforce increase its speed, strength, efficiency, and overall productivity.

California drywall subcontractor Martin Brothers recently posted a video that shows one employee using a Microsoft HoloLens augmented reality (AR) headset with a construction model loaded into it to effectively frame a drywall partition quickly and correctly without the help of other workers or using traditional tools and documents. Possible outcomes of this kind of technology include accurate as-builts and a reduced construction schedule.

Japan’s declining birthrate has resulted in labor shortages in the country’s construction sector. In response to this shortage, Japanese construction firms have turned to various forms of robotics. In addition to onsite robotic arms and other forms of worker-like robots, Japanese workers can use drones and tablet software on larger projects to drive construction equipment remotely, thereby replacing the need for multiple operators.

Whether an increase in automated solutions, use of information tools like AR, or a combination of the two, the presence of robots and automated tools on the worksite is a permanent fixture. Just like designers, construction firms and employees have to modify their expectations when considering possible solutions for building issues. They may also need to modify their bids given the potential reduction in project timelines due to more productive workers.

Conclusion

The result of AI and its appearance in the workplace is not likely to be the fully automated job wasteland that many fear. Instead it will likely conclude as most other technological advancements historically have—with a change in work habits and a renewed focus on the skilled work firms are paying for. This kind of change means you will probably need to acquire new skills with replacement by a humming box in the corner being the possible cost of not keeping pace.

To conclude, here’s a summary of what was discussed in the article:

- Increased use of AI and related methods of algorithmic analysis have already made design more effective.

- More solutions and information about design and constructability will become available as AI tools become cheaper, better-integrated, and more commonplace.

- Increased use of robots onsite will help to relieve the burden shortage of skilled workers presents and could increase worker productivity and worksite safety.

Next month, we’ll talk about the relationship between AI and the Internet of Things (IoT).

Greg Ceton, CSI, CDT, is CSI director of strategic initiatives and special projects. He lives in the D.C. area and likes disruptive technology, good food, and cats.