Offsite construction is part of a gradual move toward a more manufacturing-based process in the construction industry. As specifiers and designers may already know,

construction productivity has lagged other industry sectors tracked globally for some time, all but flatlining since the 1970s (For more information, read “Reinventing Construction: A Route to Higher Productivity,” published in February 2017 by McKinsey Global Institute). In comparison, other sectors have seen nearly three times the growth, with manufacturing, specifically, approaching four times the growth in productivity.

This is, partly, because other industries have changed their processes to take advantage of technological developments. Though there have been upgrades both to worker safety and materials, the method of delivering commercial construction has largely not changed since the 1960s (Consult “The History of AIA Contract Documents” by the American Institute of Architects [AIA] at

www.aiacontracts.org/contract-doc-pages/21531-the-history-of-aia-contract-documents and “Preservation Construction: Design-Build Versus Design-Bid-Build,” a 2010-master’s thesis by Nicholas Michael Patrick for University of Georgia.).

Offsite construction promises to reverse some of this trend, by allowing significant amounts of building construction to be performed in a controlled environment, and depending on project needs, on a near assembly-line basis. This provides benefits for worker safety and comfort, and for ensuring materials and resources are consistently available to the project team. It also allows for parallel work, with needed onsite work being performed at the same time as assemblies are prepared offsite.

I recently spoke with representatives of different offsite firms and organizations about this method of delivery, what it requires from users, and the implications for specifications, product selection, and project delivery. Many of my preconceptions were also challenged during these interactions.

Defining offsite construction

Defining offsite construction

The number of different approaches that can be called “offsite construction” is quite staggering. It includes everything from pre-engineered facilities and custom 3D modular construction to panelized approaches for walls, floors, and other systems. If there is a way to take a part out of a building, assemble it offsite, and truck it to the jobsite, there is probably a company somewhere doing just this.

Laurie Robert, vice-president of sales and marketing at a commercial 3D modular construction firm, told me the biggest differences between traditional construction and offsite projects lie more in project delivery and timeline expectations than they do in materials or means and methods.

“Offsite construction is more of a process. The role of all members on the project team—contractors, designers, product manufacturers, and owners—is very different in offsite projects because the sequencing and decision-making process is very different,” she said.

3D modular construction

When discussing offsite construction many people think of 3D modular units. This approach consists of 3D modules designed and built in an offsite facility and transported to the site where they are assembled. These modules comprise most or all of the project. However, not all assemblies in a building can be fabricated offsite, especially for large projects. Elements such as foundations or concrete masonry unit (CMU) walls, for example, would certainly be cheaper and of higher quality when assembled onsite in a traditional fashion. Even when these systems are built onsite, it is possible to transport most of the remaining building spaces and systems to the site, saving time and ensuring exposure to outside variables or shortages in available construction resources do not have a negative impact on the project quality or timeline.

Modular 3D construction can include assemblies as small as a bathroom unit or as large as a completed ballroom and even bigger assemblies if it suits the project. The only limits are the ability to truck the modules to the site and the comparative cost in time and money of doing that part of the work in a traditional onsite fashion.

The limits of transportation cannot be overstated.

“Mechanical system size due to either ductwork or the equipment may cause transportation issues. This may also provide a limit for module ceiling height in some cases depending on where they are being transported. The choice (between modular and traditional) may be driven as much by location of the building site and available resources there as anything,” explained Robert.

From a specifications perspective, if a modular company received a set of contract documents for a traditional building, it could use them to convert the project to an offsite process. In this case, the role of the specifier would be very similar to his or her role in a traditional construction project.

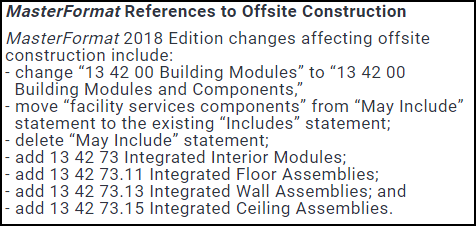

“The chief difference is in stating the means by which the modules will be created,” said Robert. “The specifier could use Divisions 13 or 01 to establish construction requirements, and the specifier will also have to, in conjunction with other project team members, identify how and what will be constructed on- or off-site.”

Scope of work becomes important

The modular company will typically take on design and execution of structural and foundation requirements even though these elements are typically site-constructed. Regarding product selection, some companies take into account designer or owner preferences as well as offer alternatives that work better in an offsite process.

In this respect, the modular supplier acts as a large subcontractor. This makes the scope of work document very important, enabling the offsite work to be easily passed to the general contractor (GC) with clear instructions on what is expected. The offsite supplier and the GC may also share execution and procurement requirements and administration. It is of utmost importance to have a clear understanding of what the scopes of work are for each participant to avoid duplication of effort, resulting in added expense and waste. This means a heavier lift for the architect at the project start, as the architect and the owner are responsible for decisions that must be finalized before offsite production starts, earlier than often happens with traditional construction.

From the owner’s perspective, with any type of offsite construction, the chief savings are in project timeline, and not direct material costs. Since work can be performed simultaneously on- and off-site, there are zero weather delays in offsite construction, and far fewer change orders, the result in most cases is a significant trimming. This can sometimes be as much as 50 percent of the delivery timeline for the section of work in question or the project as a whole.

Panelized solutions

Another approach to offsite construction involves the assembling of specialized wall or intra-wall panels, including piping, HVAC components, and wiring, for later installation or assembly at the jobsite. This method presents less of a transportation challenge than 3D modular construction, and provides a method for doing what can be complex and expensive work in a controlled environment. This helps ensure both quality and schedule for delivery of these assemblies, which in some projects, like healthcare or hospitality facilities, can be a significant portion of the initial investment and the construction project schedule.

David Parrish, mid-Atlantic team lead for a module interior systems manufacturer, indicated that although many people think of his firm’s panels as a product, “What we offer is not a product; it is a process, a method of construction with automation.”

To accommodate the process, a Division 13 integrated construction section “could be written almost like a pick list from which specifiers, designers, or owners could deselect some options almost as one would do with a master guide specification,” he added.

For me, one of the most interesting aspects of some of the modular and panelized solutions I witnessed was the non-proprietary nature of the systems. Some of the firms made it clear if there was an owner or designer preference for a product or approach, it was easy to make their solution fit that need. One of the companies I interacted with manufacturers panels that can be either demountable or permanent, and can be modified over time as needed, as the company believes it is important to not tie the owners’ or facility managers’ hands and instead allow more or less universal connectivity for the panels.

As with other forms of offsite construction, gaining widespread acceptance of panelized offsite construction has been a struggle.

“Typically,” said Parrish, “only because of duress of a tight schedule or a tight site, or other limiting circumstances, do general contractors or architects turn toward offsite solutions.”

Beyond the pressure, offsite construction is just not considered by most GCs. Further, as Robert recounted a statement made by an architect to her, “The next time I have to build a box, I will call you.”

“Of course, this is not the case,” she continued, “offsite construction can have flair.”

Owners are often the ones pushing for use of offsite solutions, chiefly because a shortened timeline provides a significant offset for any cash difference in initial expenses incurred from offsite construction. This is why different types of modular construction have been so popular in the retail and fast food industries, and what has led to its use in other sectors needing rapid market presence, such as ambulatory care facilities.

As Parrish said, “The quicker they can stand an urgent care center up, the sooner the owner makes money.”

It also takes pressure off emergency room services which the owner may also be providing in the area.

“The return from the urgent care facility can be a million dollars a month,” added Parrish.

The type of panels being produced by offsite construction companies can get the building operational faster than the usual timeline. The impact of the sudden appearance of a building onsite also provides a great marketing advantage.

Changes to scopes of work

Aside from the delivery differences mentioned above, the chief difference imposed by offsite construction is an impact on project team roles and timeline. Among other things, offsite construction forces the project team to engage in “big room” style decision-making at an earlier stage in the project than designers may expect. This type of approach means the GC and subcontractors will be brought in with the offsite construction supplier, designers, and owner representatives to help ensure everyone understands their role, deliverables, and scope of work, as well as what to expect and when. In an ideal case, it would also include design consultants like specifiers to help ensure they are also on the same page with project timeline, budget, and performance requirements. The specifier can also offer inputs on any product or assembly selections the offsite supplier will be recommending.

This process forces the kind of early decision-making being promoted recently in discussions of integrated project delivery and building information management (BIM), as described by what has come to be known as the MacLeamy curve (Figure 1). Early decisions reduce costs, change orders, and generally make the project run more smoothly by exposing shortcomings or incorrect assumptions while there is still time and resources to correct them. Unfortunately, this process can present an obstacle for many design firms’ culture, but the fact that offsite projects force this sort of behavior is one more reason why they tend to reach completion quicker than projects delivered by traditional means.

Figure 1: The MacLeamy Curve shows how cost of change rises, and the ability to affect project outcomes shrinks as one delays finalizing decisions. Provided with permission from www.danieldavis.com/macleamy.

The future of offsite construction

Tom Hardiman, executive director of Modular Building Institute, expects modular and offsite construction to become a predominant option for owners in the next five years, especially for owners like healthcare providers and hotel chains. He indicated they were already seeing this trend around worldwide.

“I think it is inevitable. The United Kingdom has already made major strides here. Australia and Singapore are moving towards modular high rises to address housing issues. In some areas in the United States, such as New York or San Francisco, the high housing costs coupled with high labor costs and smaller construction labor pools will drive developers toward modular construction,” said Hardiman.

As this takes shape, Hardiman also sees a move toward the construction-as-manufacturing model.

“What the industry is currently doing is just moving the work location for what is still largely traditional construction. Some companies have started to move more towards industrialized construction with a little more automation, and that is where the offsite future lies. As that becomes more predominant, cost and productivity gains will certainly drive our industry closer to a true manufacturing-style process,” he explained.

Hardiman chairs the National Institute of Building Sciences (NIBS) Off Site Construction Council (OSCC). The focus of OSCC’s work now is to produce guidelines to help promote a broader understanding of offsite construction. OSCC is working on two products.

“The first is a design guide with the American Institute of Architects [AIA], aimed at helping architects overcome some of their presumptions about offsite construction. The second is a guideline with the International Code Council (ICC) aimed at code officials to help them understand how to administer code requirements in an offsite project,” he said.

Additionally, OSCC is interested in learning more about the needs of CSI members to help ensure, as offsite standards and other requirements move forward, they can be correctly and completely implemented by practitioners.

Greg Ceton, CSI, CDT, is CSI Director of Strategic Initiatives and Special Projects. He lives in the D.C. area and likes disruptive technology, good food, and cats.